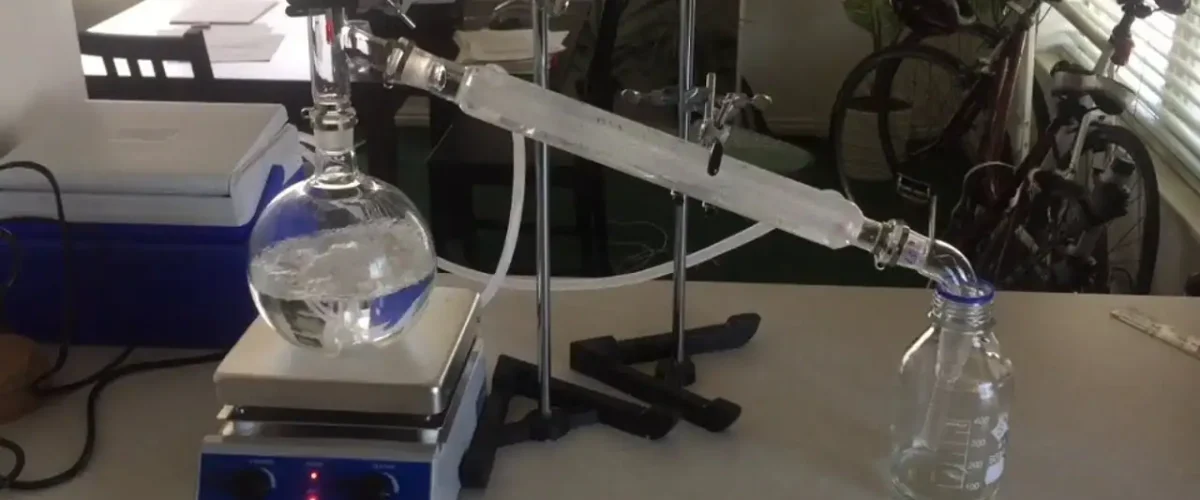

Distillation is a classic way to separate liquids based on their boiling points. However, with ethanol, there’s a natural limit: no matter how efficient the system, ethanol can’t be purified beyond about

The cause? Ethanol forms an

In this article, we explain what an azeotrope is, why ethanol “gets stuck” at 96%, and what additional techniques the industry uses to produce absolute (anhydrous) ethanol .

What is an azeotrope?

An azeotrope is a mixture of two liquids that has a fixed boiling point and does not change composition during boiling. The vapor released has exactly the same ratio as the liquid.

In short:

- The mixture boils as if it were a single substance.

- You cannot separate it further by distillation.

- This is caused by strong interactions between the molecules, which means they no longer behave “ideally”.

When a mixture forms an azeotrope, normal distillation ceases to work, even with perfect equipment.

The Ethanol–Water Azeotrope: Why 96% Is the Limit

Ethanol and water form a special constant-boiling mixture (an azeotrope) when:

- 95.6% ethanol

- 4.4% water

This mixture boils at about 78.2°C, just below the boiling point of pure ethanol (78.37°C).

Why is this important ?

Because this azeotrope has the lowest boiling point in the mixture, it behaves differently than a normal mixture:

- The composition of the vapor = composition of the liquid

- Both liquids evaporate together in a fixed ratio

- Further distillation does not change the purity.

From this point on, the mixture behaves as a single substance. Therefore, conventional distillation can never yield more than ~96% ethanol.

Why distillation stops at the azeotrope

Distillation relies on differences in volatility. Ethanol is normally more volatile than water, so in the early stages of distillation, the ethanol purity increases easily. However, once the azeotrope is reached, this separation power disappears.

The mixture has then reached vapor-liquid equilibrium at which:

- The boiling point is constant

- The composition is constant

- The vapor is no longer “richer” in ethanol

It doesn’t matter how long or how intensively you perform the process: the purity remains around 95–96%.

Why industry still needs more than 96% ethanol

Industrial facilities require ethanol in varying degrees of purity. 96% ethanol (also called

- Absolute ethanol (99–100%)

- Anhydrous ethanol

- Anhydrous ethanol for moisture-sensitive reactions

Because distillation cannot break the azeotrope, the industry uses additional drying methods, such as:

- Molecular sieves

Porous solids that adsorb water molecules while leaving ethanol behind.

They can increase ethanol purity to over 99.9%. - Azeotropic or extractive distillation

In this process, a third substance (an entrainer ) is added to alter the cooking behaviour and break the azeotrope. - Vacuum distillation

Adjusting the pressure changes the cooking properties, which aids further separation.

These techniques produce ethanol that is completely anhydrous and suitable for industrial and laboratory applications.

Commercially available standard purities of Ethanol

Ethanol is available in various purity grades, depending on the application and regulatory requirements. The most commonly used commercial concentrations are:

Ethanol 70%

This concentration is often used in environments where a diluted alcohol solution is required, such as for general cleaning or laboratory applications where a lower alcohol strength is sufficient. The water-to-ethanol ratio allows the liquid to reach certain surfaces better than higher concentrations.

Ethanol 96%

This is the most commonly used high-purity grade in industry and laboratories. Ethanol 96% (rectified spirit) is produced via standard distillation and approximates the natural maximum of the ethanol–water azeotrope. It is suitable for a variety of technical and industrial processes requiring a nearly anhydrous alcohol.

Summary

Ethanol cannot be distilled above 95–96% because it forms a constant-boiling azeotrope with water. At this composition, the vapor and liquid have the same ratio, so distillation does not work any further.

The azeotrope has a slightly lower boiling point than pure ethanol, causing the mixture to behave as a single substance when boiling.

To obtain anhydrous ethanol, industries must use additional drying steps, such as molecular sieves or specialized distillation techniques. This chemical limitation is fundamental and applies to all distillation systems, from laboratories to large-scale industrial facilities.